What is Lab Lit, and Why Should You Read It?

Category: Biblio-File

Calligram. Hardboiled. Bizarro. Wuxia. Bitpunk. Furry sleuth. Slipstream. Canadiana. Bangsian. Penny dreadful.

What do these terms have in common? You’re not alone if you had no idea. They are all examples of microgenres – highly specialized, niche subgenres of literature popular somewhere in the world today. Each microgenre has its own specific tropes, styles, and characteristics, making it unique and recognizable. Most microgenres have a small but intensely dedicated audience of readers who identify with cultural aspects of the works.

Introducing Lab Lit

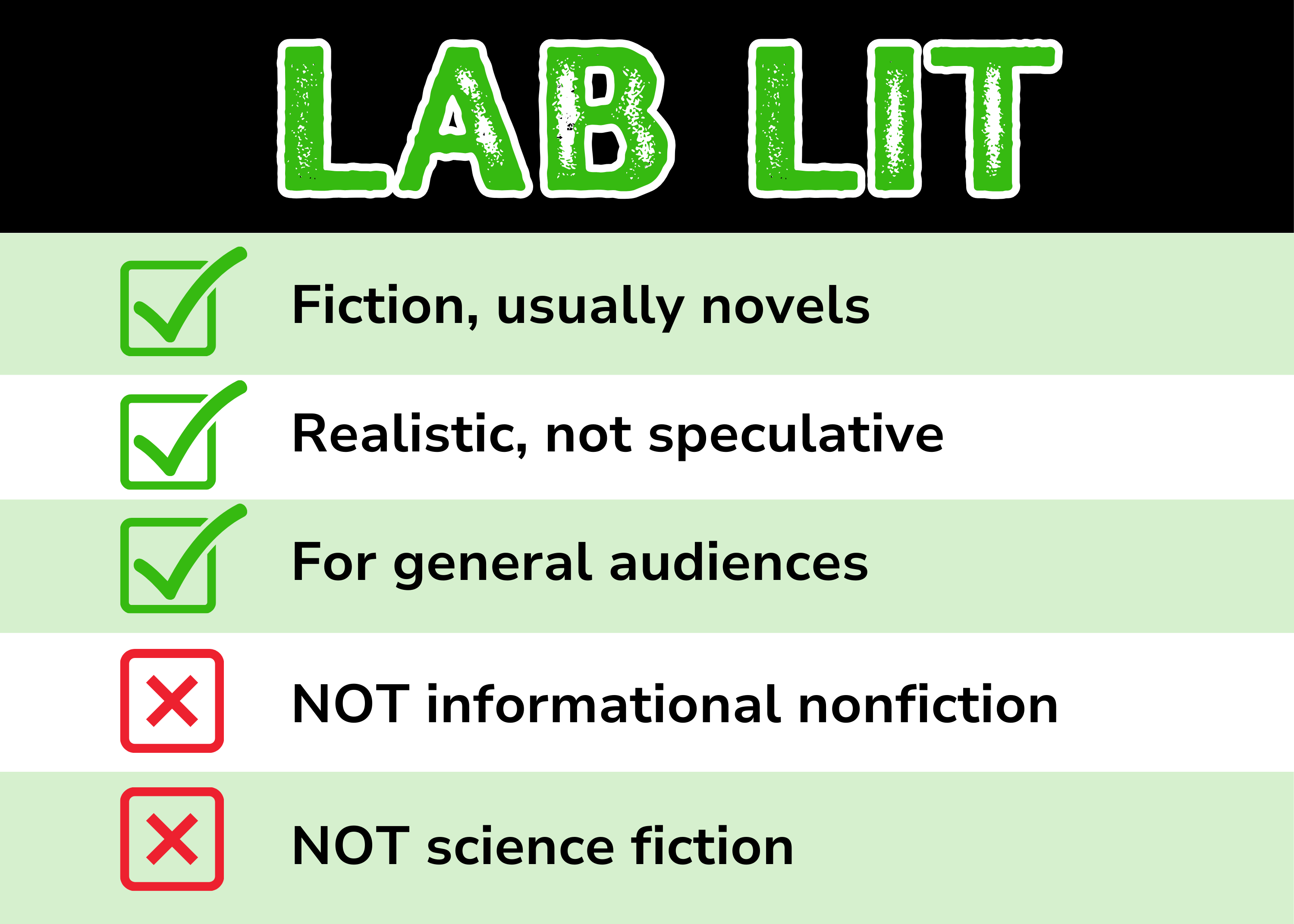

At Diverse STEM Books, our audience is exactly that – intensely dedicated readers of science writing. That’s why we’re excited to introduce you to a terrific STEM-related microgenre: lab lit. The name is short for “laboratory literature,” but it’s not part of the science fiction space. Rather, it’s realistic in setting, realistic in characters, and realistic in the portrayal of science.

Sci-fi, of course, does not stick to the world of the possible. That’s the appeal. Sci-fi is speculative–not always set in the future, but mostly, and always in scenarios that are not part of the universe as we know it today.

Lab lit, however, is part of the everyday world. The events portrayed could conceivably occur in our regular world. Lab lit stories fall under one of two larger categories: contemporary realistic fiction – if it’s set in the present, or historical fiction – if it’s set in the past.

The characters just happen to be scientists, and the plot just happens to center on science. An example of a contemporary lab lit tale would be a novel about a researcher at a genomics lab making a critical discovery. A historical lab lit tale could be a fictionalized retelling of the events surrounding a significant invention from a past century.

Despite the name, lab lit does not have to be set in a lab. But it does cover the work that scientists are doing, whether in a remote field station, a university, a company, or a personal workshop.

What’s in a Name?

Like many of the microgenres mentioned in the opening lines, lab lit is mostly a recent phenomenon. After all, the term “scientist” itself is relatively new to the scene. William Whewell coined the term in 1834, and it took time to catch on.

Before that, there was natural philosophy, not science, and the people who practiced it were called natural philosophers. [For more content on science and scientists of past eras, see our blog entries in the “History of Science, Future of STEM” category.]

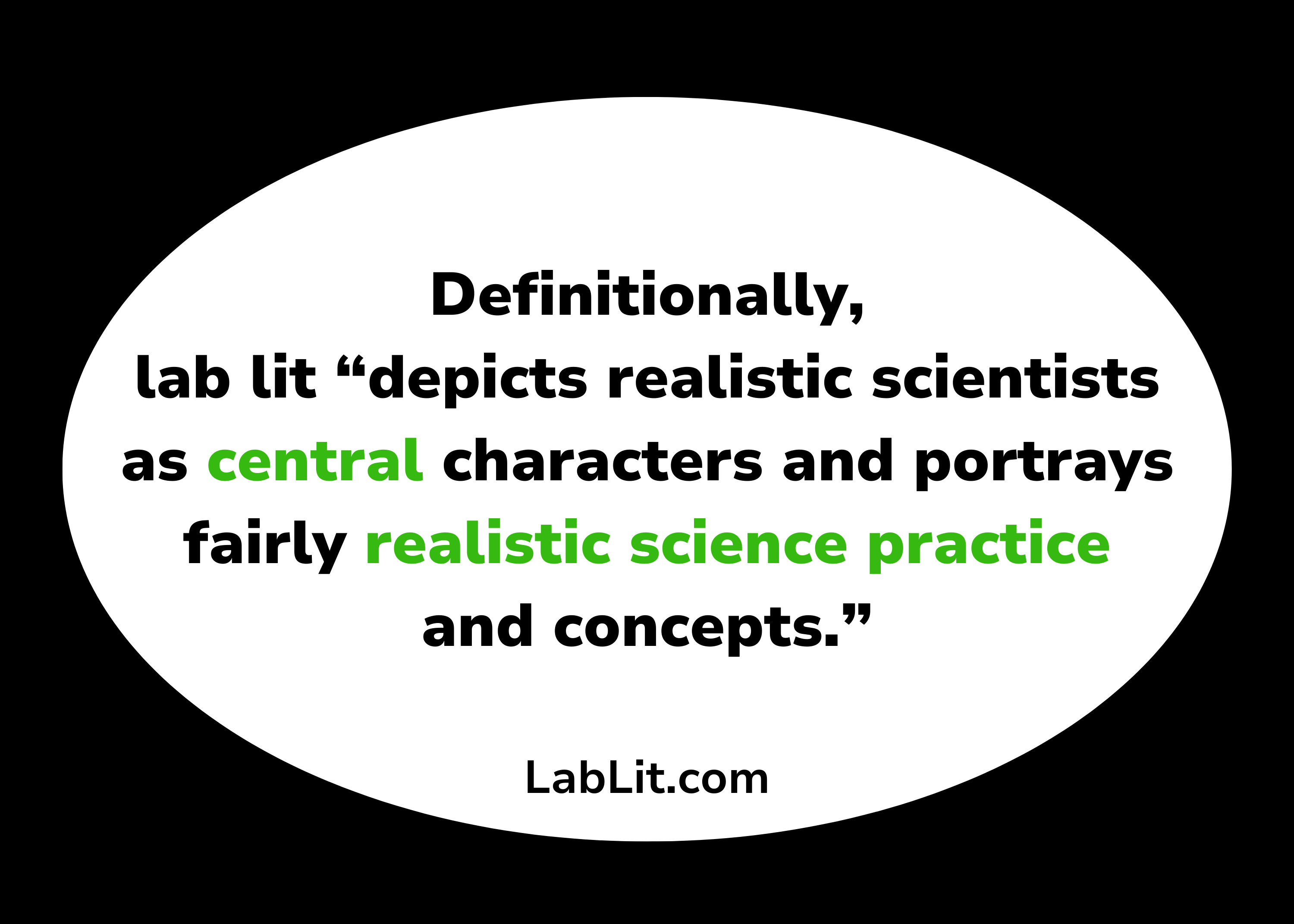

Fast forward to 2001. Jennifer Rohn, an American-British microbiologist, first used the term “lab lit” to describe the kind of science-themed novels she gravitated toward and eventually wrote herself.

Lab Lit, the Webzine

Then in 2006, Rohn founded the site LabLit.com, “dedicated to real laboratory culture and to the portrayal and perceptions of that culture – science, scientists and labs – in fiction, the media and across popular culture.”

Notice the way she uses the word “real” in her description of lab lit. She uses such depiction in her own writing. Rohn is the author of three lab lit novels, short fiction, and opinion, as well as academic publications in microbiology.

Lab lit is intended for general audiences. No specialized knowledge is presumed. Some scientists enjoy reading it because the subject reflects their interests, but lab lit is written to be a window into the practice of science that the public at large can understand and appreciate.

Who Writes Lab Lit?

Authors of lab lit, like writers of any books, come from all kinds of backgrounds. Some lab lit is written by practicing scientists, and some by authors with no particular STEM or technical background.

- Non-Scientists

The best examples of lab lit come from both categories. Best-selling novelist Barbara Kingsolver published Flight Behavior in 2012 to great acclaim. The book is often cited as an exemplar of lab lit. “Ms. Kingsolver uses fiction to advocate for environmental awareness via a plot driven by science: ‘an entomologist tracking the effects of global climate change on monarch butterflies,’” according to Science Times book reviewer Katherine Bouton. Although Kingsolver’s body of work commonly features environmental themes, she is not known primarily as a lab lit author.

- Practicing scientists

By contrast, Carl Djerassi is an author whose body of work falls squarely within the domain of lab lit. A practicing research scientist who is known as “the father of the pill” for his contributions to hormonal birth control technology, Djerassi used his familiarity with the world of pharmaceutical chemistry in his writing. A prolific author, he penned not only novels, but also short stories, poems, memoirs, and plays.

Djerassi himself used the term “science-in-fiction” to describe his work. Most of his work was published well before the term lab lit had been coined in 2001, but it is clear that his intent was to produce culturally relevant narratives that contextualized the work of scientists, and to do that for the general public, not a specialized audience of fellow scientists. “I’d like to leave a cultural imprint on society rather than just a technological benefit,” he opined in a 1985 interview. Much of his work explored the ethical dimensions of scientific research.

- Recovering Scientists

Author Brandon Taylor represents a third type of lab lit author. Whereas Kingsolver is a non-scientist who occasionally writes lab lit, and Djerassi is a notable scientist, all of whose fiction falls entirely within the lab lit space, Taylor writes in both lab lit and other genres.

Trained as a biochemist in a doctoral program, Taylor eventually left the program and the field. Now a full-time, award-winning writer, his biochemistry background gives him both insider and outsider status regarding professional science.

Taylor’s published work includes both lab lit and other genres. Most notably, his debut novel Real Life, shortlisted for the Booker Prize,is set in the world of science and scientists, but most of his subsequent writing is dedicated to other subjects.

His perspective as a queer Black man from the South shapes his lab lit and other writing. Taylor centers the narrative on the practice of science and the culture of academia in a different way than do Kingsolver and Djerassi. “I didn’t write this book for the white gaze,” he notes in an interview with the Guardian: Instead, “Taylor hopes Real Life makes black readers feel seen.” Bringing a new audience to the world of lab lit is itself an exciting expansion of the genre.

Why Read Lab Lit?

Whether written by an astronomer or a novelist, lab lit brings the reader into the world of practicing scientists and their concerns. Lab lit makes the reader consider the driving principles of scientific endeavor. It asks readers to analyze and appreciate the aspects of science that have made our modern world what it is.

True scientific literacy is a key skill for the 21st century, both for professional development and everyday life as a contributing citizen in an increasingly technologically driven world. We are increasingly dependent on science and technology for the quality of lives we lead, yet the public understanding of those topics is minimal at best. Scientific literacy comes from learning science; however, reading books about science and scientists is an ideal start, especially for people who are not currently in the education stages of life. Reading lab lit is an accessible way for non-scientists to get a peek into that world, a point of entry for the rest of us. [For multiple scholarly perspectives on the scope and nature of the lab lit genre, see Lab Lit: Exploring Literary and Cultural Representations of Science, edited by Olga and Ace Pilkington.]

Who Doesn’t Like a Good Yarn?

While novels don’t directly instruct like informational books do, they offer more accessible windows into a scientific frame of mind. They offer glimpses into real-world processes and scientific practice. They offer realistic depictions of how discovery takes place and knowledge is advanced. At their best, they offer models of rigorous thinking along the lines of the scientific method.

Really, the question is why shouldn’t you read lab lit? This genre has all the drama and pathos that make for great literature in any area, as Rohn notes: “Science has it all: intrigue, curiosity, colour, competition, jealousy, rivalry, the joy of discovery and the agony of rejection. Bringing it to life on the page will help foster an understanding of what it is that scientists do and why it’s important.” There are many thrillers within the genre and certainly just as many page-turning plots as readers would encounter anywhere.

Take, for example, the first book review on DSB. Mosquitoes Don’t Bite Me is a YA novel that not only meets DSB criteria of meaningful representation and quality science content, but also a gripping plot in which the main character finds herself in physical peril and must struggle to regain her life as she knows it.

The book was a shoe-in for inclusion because it is a great read for YA audiences and even adults. It’s entertaining and high-interest in a way that would draw in even reluctant readers. Taking place on two continents and full of activity and drama, its action would be easy to translate to the big screen as an action and adventure film, for instance.

And YA audiences will learn to appreciate several scientific topics along the way. Science and literature are both modes of understanding. In the best lab lit, like this book, they complement each other.

Lab lit has substantial benefits to both individuals and to society at large in developing an appreciation for science and its methods. And it can be great fun along the way, especially for the curious at heart. Dive in to the pages of a lab lit title soon. For some inspiration on specific titles, check out DSB’s Books page. Lab lit appears under Fiction, of course, and most but not all is written for adults. Best of all, send us your favorite lab lit titles so we can keep our lists up to date!